At the end of Stage 5 we were in Porticcio, a few kilometres south of Ajaccio on the south-western coast of Corsica. We were half-way through the challenge and I was badly in need of a rest day. I had ridden 848 km and climbed 20,500m in five days, cycling a little over 9 hrs per day (not including the stops). Three of my companions had dropped out completely. Click here to read my account of the first five stages.

How would my body hold up over another five punishing stages? Read on to find out…

Rest day

Sleep, glorious sleep! For the first time in five days I was able to get a good night, untroubled by the need to rise early, shovel down a quick breakfast and be on the bike by 07:30. I sauntered down late and then lingered deliciously over a huge breakfast at the hotel buffet.

The day’s programme was simple: laundry, massage, clean the bike, physio appointment, lunch, siesta, recovery ride, dinner. It reminded me of “make and mend” days from my early career in the Navy, and felt luxurious, even hedonistic after the Spartan endeavours of the previous five days.

The massage was in the hotel. It was heavenly, warm and oily, deeply relaxing as she gently teased the knots out of my tired muscles. Soothing music was playing and I lay in dappled sunlight, filtered by a palm tree just outside the window, just happy to soak it up and let the fatigue seep out of me. As always, it finished way too soon. How could an hour flash by so quickly?

By comparison, the physio appointment was a more workmanlike affair. The therapist had the build of a rugby player and after stretching me in all directions he got much deeper into my quads, forcing me to writhe on the table and suppress yelps of pain. It was a relief when he said my time was up.

I did a short post-siesta recovery ride, mostly easy on the flat, just to spin the legs and get the blood flowing. I was surprised and rather alarmed to feel quite sharp pains in my right knee and left Achilles tendon, but both seemed to get better after 20km. Was this a sign of things to come, or just a passing twinge?

Stage 6 Loop around Porticcio: 164km 3,210m

Today was a loop stage so there was no need to pack and bring down the bags, and I was able to leave my laundry drying on the balcony. In the real world it was Friday, but it was definitely not a case of TGIF. To me it felt like Monday morning and back to work. Once more unto the breach, dear friends!

Stage 6 profile

Stage 6 profile

We rode the first 14km south on the flat along the beach, the pace moderated by Phil so we all stayed together. I took the opportunity to chat with two riders who had joined us late last night. Both very experienced CCC riders, they had a special pass to join mid-Challenge. One lives close to my own home so we spent a pleasant few minutes trading favourite climbs.

The flat didn’t last of course and we soon turned left and began the first climb, to the col de Gradella (529m). The first 3km were lined by eucalyptus trees, their trunks lacerated, the multi-coloured bark coming off in long thin strips like shredded paper and littering the side of the road in russet, pink, white and shades of brown. The climb was exposed to the west and there were signs of serious winter storm damage, with many broken and uprooted trees.

The good news of the morning was that my knee and tendon seemed to be OK. I wasn’t taking any risks, however, and rode at an easy pace throughout the day.

After about 3km the road entered dense maquis, the typically Corsican mix of low trees and shrubs, from where we only had occasional glimpses of the sea through the thick vegetation. The group quickly split on the climb. The fast riders were completely untouchable, but even the middle group set a higher pace than I wanted, so I was happy to bumble along on my own, taking my time to observe and enjoy the surroundings. Strawberry trees were overhanging the road, their branches laden with yellow fruit turning red, and invitingly scarlet ripe fruit was lying in the road, just waiting to be picked up by a jay or a passing cyclist.

In places the trees touched overhead to form a dark green tunnel, with little light filtering through. The stagnant air was heavy with the earthy scents of the leaf litter and undergrowth, the only sounds from my breathing and my tyres on the road. Elsewhere we broke out into the open with the sun in our eyes. It’s a consequence of cycling from the west coast: you have the rising sun in your eyes in the morning and the setting sun in your eyes in the evening. It’s a small price to pay for the outstanding natural beauty of the west coast.

The first feed station was on the col de St Georges (757m). We stopped in a layby off the road, not far from a café. I ate two large bowls of Phil’s delicious overnight soaked muesli and stuffed my pockets with honey waffles. If I was going to be unable to finish the Cent Cols Challenge, it certainly wouldn’t be because I didn’t eat enough.

The gulf of Ajaccio, from above Ocana

The gulf of Ajaccio, from above Ocana

I loved the descent, on a main road with fast sweeping bends, but all too soon we turned off onto a tiny single track road and descended much more slowly for another 4-5 km before the next climb. This turned out to be a delight, with increasingly open views as we gained height to the Bocca di Mercuju (726m). We passed through a village named Ocana on the way, which made me think of the Spanish cyclist with (almost) the same name. Like Laurent Fignon, Luis Ocaña is more famous for the Tour he lost (1971) than the Tour he won (1973).

We skirted the Tolla lake, a beautiful deep blue sparkling beneath cloudless skies. The lake is artificial, created by a dam built in the gorges du Prunelli in the 1960’s for hydro-electric purposes, but has integrated well and looks natural, in spite of the low level.

Tolla and its lake

Tolla and its lake

After over 90 kilometres of good roads, the first 3-4km of the descent were a shock. The road had been patched multiple times, and I was forced to endure another bone-shaking, brain-scrambling descent, gripping the bars, fighting to keep control of the bike, trying to strike the right balance between too much speed and constant braking, picking a careful line between the worst of the holes, all the while swearing under my breath.

I passed by a large herd of beautiful long-haired goats, sadly without stopping to take a picture, and then had a close call with an articulated truck. I was descending in the gloom under the trees and arrived at a dark hairpin corner just as the truck was using the whole road to get round, forcing my heart into my mouth and me onto the shoulder.

The author, on the col de Scalella

The author, on the col de Scalella

After 6 hours of riding I reached the highest point of the day, the col de Scalella (1,193m). The road wound up through pig farms in a heavily wooded area, and there were signs everywhere of the thunderstorms we encountered on Stage 5. Piles of sand and gravel were washed out onto the road, together with small branches, twigs and leaves. I wove a path around the worst of it, my tyres crunching over the sand, happy to be climbing and not descending.

Cuttoli-Corticchiato, in the late afternoon sun

Cuttoli-Corticchiato, in the late afternoon sun

The ride continued on quiet secondary roads. We passed through the occasional hilltop village (Carbuccia, Peri, Salasca, Cuttoli-Corticchiato…), all tiny, but always built in the same way, the massive, ageless granite houses close together and grouped around the church. On the outskirts of the villages the houses often had kitchen gardens and fruit trees. As well as apples I saw several persimmons, the fruit still yellow and ripening slowly.

As so often in Corsica, the views were breath-taking, with the sea in the background for the final 20km or so.

The long and winding road

The long and winding road

We were back at the hotel before 5pm, less than nine hours after leaving in the morning. Almost a recovery day! Sixty-two cols ticked off, just 38 to go.

Stage 7 Porticcio to Porto: 199km 4,910m

Stage 7 was the Queen stage.

The profile sticker Phil gave us at the briefing last night looked like he’d scribbled it in a rage – I counted 22 separate spikes in a vicious-looking saw tooth pattern. (The profile below reproduced from Strava looks slightly less dramatic). To add to the ambiance, there were dire predictions that the estimated climbing was wrong (the sticker announced 4,520m) and we would in fact be doing 200km and well over 5,000m. In other words, more than the Marmotte. And yet this was Stage 7!

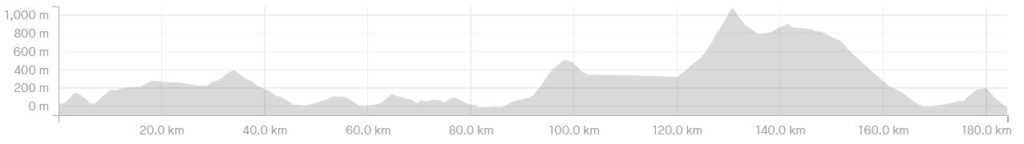

Stage 7 profile

Stage 7 profile

Mindful of this, I decided I’d be better off sleeping a few extra minutes rather than walking the considerable distance to the dining hall and back for breakfast. We were due to start at 07:30 and we were changing hotel, so all had to be packed and the bags brought down early. I ate left-overs from last night’s dinner in my room while packing my bags and getting ready.

Dawn was just breaking as we left, our red bike lights flashing in the gloom, the flowers in the suburban gardens still dull in the half-light. Nobody spoke. My legs didn’t feel good, but then they rarely do at the start. More worryingly, the first couple of hours were spoiled by the return of the pain in my left Achilles tendon. It was not helped by one of those horrendously steep little climbs at km 20. Not long, but enough to expose any lingering weakness and instil doubt for the rest of what would be a long day.

Soon after this we were on to the first significant climb of the day, the col de San Bastiano (411m). This was another of the climbs used by the Tour de France in 2013, this one on Stage 3, from Ajaccio to Calvi. Like most Tour climbs it is on a main road and the gradients are thus rather unremarkable, although there was a splendid view across the Golfe de Sagone.

It was Saturday morning so the hunters were out in force once we left the main road and started up the climb to the Bocca di Sarzoggiu (612m).

Strawberry tree (Arbousier, Arbutus unedo)

Strawberry tree (Arbousier, Arbutus unedo)

I have never seen so many strawberry trees. Fruit lay all over the road and I passed one of the hunters eating a handful of bright red berries, his gun casually slung over his shoulder. A bit further up I spotted a low-hanging branch and stopped to sample the fruit. Looking rather like litchis, the taste is closer to strawberries, tart and sweet but less flavoursome and slightly gritty from the skin and seeds. I have never seen them sold to eat as such, but the Corsicans make a sort of jam out of them (Gelée d’Arbouses) which can be purchased in the local shops.

More climbs followed. The climb to the col de Tartavellu (885m) was nice and steady, never steep, on a quiet secondary road shaded by pine trees. There was no transition to the Prunelli: we reached the bottom, crossed an attractive old stone bridge and started straight up again. The Prunelli is quite a bit steeper than the Tartavellu and my right knee started to hurt, which was worrying.

We cross the bridge over the river Cruzzini, near Giradaja

We cross the bridge over the river Cruzzini, near Giradaja

Over the top my companion and I startled a litter of fat little piglets on the road. We laughed out loud as they ran in all directions in a clownish panic, turning back on each other, falling over each other and rolling over comically, all the time squealing loudly. If only we could have filmed it! It was a made-for-social-media moment that would surely have brought us our 15 minutes of fame.

The village of Rosazia

The village of Rosazia

We made two more climbs before Murzo and the second feed station: an out-and-back which took us over the col de Sorru (624m) and up the Zoicu canyon (1,008m). This last was a steep climb above the village of Soccia on a single track road, to a dead-end and a gravel car-park. There was nothing obvious of interest up there, but perhaps I was past caring. (I learned later that it was a popular spot for canyoning in summer). By now my knee had stopped hurting but every other part of me was protesting. Lunch came not a moment too soon.

On the way to Murzo, looking back on the D4

On the way to Murzo, looking back on the D4

The final effort up to the col de Sevi (1,101m) was very long: 22km, broken by two short descents but otherwise relentless. The last two km were especially hard at 11-12% average, touching 15% in places. It would only be a minor understatement to say that I was relieved to reach the top. The end was in sight, metaphorically at least, because all I had to do now was descend down the Gorges de la Spelunca for another 20km.

This would have been a stunning descent to do earlier in the day. The road wound haphazardly and unpredictably in and out of the gullies and ravines in the side of the main gorge, with only a low stone parapet to protect from the precipice. It was well after 6pm, the sky was rather overcast and the light was failing. It was not the moment to practice high-speed, high-risk descending, but even at a more moderate speed it was sadly too late and too cold to enjoy it. As if to emphasise the point, my right Achilles tendon was now playing up, keeping the left one company.

I arrived in the tiny port of Marine de Porto at about twenty to seven, not long before dark. I was very tired and cold, I felt broken and battered as if I’d played all day in a rugby tournament, and I had definitely had enough for the day. The Queen stage was done, but my body seemed to be saying: Enough!

Three more stages to go…

Stage 8 Loop around Porto: 167km 3,620m

Porto, or more exactly Marine de Porto where we were staying, is a tiny village consisting almost entirely of small hotels and café-restaurants by the water’s edge. It was all constructed in the twentieth century to cater to the summer tourists. The original village is Ota, which is in a much more defensible position out of sight from the bay, 5 or 6km up the valley and at altitude. The whole area is a UNESCO world heritage site due to the natural beauty of the Gorges de la Spelunca and the Calanche de Piana, both of which we were to see today.

Stage 8 profile

Stage 8 profile

I was delighted to learn that the ride would start by going back up the gorges we had come down the previous evening. It was one of these stunning roads for which Corsica has the secret, and cold and tired as I was, I really couldn’t do it justice in the descent. It is part of the longest continuous climb in the island: 34km from sea level all the way up to the Bocca à Verghju or col de Vergio (1,477m). It’s also the first time on the island that we have seen kilometre markings for cyclists. Perhaps a sign of things to come? With the right infrastructure, the island has the potential to give Mallorca a run for its money.

I started easily and enjoyed the early part of the climb through a forest of chestnut trees. Many of the trees had dead, broken branches or shattered tops, probably again a testament to violent winter storms. I could well imagine the force of a westerly wind here, focused and funnelled up the gorge by the surrounding cliffs and lashing the exposed trees mercilessly.

This being Corsica there is a pig farm halfway up, the delicate perfume as usual detected by my nose some 200m in advance. A large boar had an important air about him as he went about his business, not deigning to pay me any attention. Piglets rooted busily around in the undergrowth.

I was delighted to find myself in very little pain this morning, in spite of yesterday’s huge stage. All systems seemed to be functioning correctly once more. I wasn’t sure whether to attribute this happy state of affairs to my body finally adapting to the load, or to the large dose of Ibuprofen swallowed last night and again with breakfast. Either way, things were good!

In the Gorges de la Spelunca, on the climb to the col de Vergio

In the Gorges de la Spelunca, on the climb to the col de Vergio

The higher parts of the gorge are even more spectacular than I remembered. The rock formations are of pink granite, weathered and blasted into fantastic shapes. The cliffs are sheer, the vegetation olive-green and sparse, clinging tenaciously to tenuous footholds in cracks and crevices. There was not a cloud in the sky, and the deep blue of the sky contrasted beautifully with the pink and orange rocks and the green tones of the scrub clinging to them. At a bend in the road at about 800m up I could see all the way back down the gorge and out to sea. The sea was the same deep blue as the sky, but curiously the sky lightened near the horizon, thus marking it out clearly.

The Gorges de la Spelunca and the village of Ota

The Gorges de la Spelunca and the village of Ota

I stopped at almost every corner to take pictures. As I am sure you will understand, this is the main reason why I didn’t trouble the KOM on the Strava leaderboard for the climb, taking almost 2h and 20 minutes to reach the col.

In spite of the sun it was chilly on the col and we quickly put on warm clothes for our second breakfast. Luckily the wind was light, for it was a very cold descent, fast and mostly in the shade, and I needed an extra jacket and long-fingered gloves to be comfortable. It was a luxury to be able to get these from the support car and return them again at the start of the next climb. It’s important not to be totally dependent on the support, but it adds appreciably to the comfort of long rides such as these.

Second breakfast on the col de Vergio (1,477m)

Second breakfast on the col de Vergio (1,477m)

The semi-domesticated animals that we often crossed on the roads were a great source of comic relief. There was another hilarious one in this descent: a fat, hairy pig was scratching its belly on a log, reminding me of Baloo the bear singing the “Bare Necessities of Life” in the Disney cartoon film of the Jungle Book. Forget about your worries and your strife… Now there’s a good theme for a Cent Cols Challenge!

We shared the climb to the col de Sevi (1,102m) with the participants in a local sportive. Needless to say, they were climbing faster than we were. It was instructive to see the difference between the elite riders in front and the others at the back: a smooth, elegant and powerful pedal stroke for the first, a more jerky movement for the second, pedalling in squares, kicking on the down-stroke, rocking the shoulders, tugging on the handlebars… The French, as ever ready with an apposite image, call this “pedalling with your ears”.

It was a fast descent on the other side and I had fun keeping up with the sportive riders, almost missing a turn where our route went left and theirs went straight on. Ooh la la, wake up!

Coffee stop in Mercolaccia (360m)

Coffee stop in Mercolaccia (360m)

We found a charming little café in the village of Mercolaccia. It would have been a crime not to stop here.

The small col at Ambiegna had large groves of olive trees and the first vineyards I remember seeing, producing wines with the Ajaccio AOC label. No, we didn’t stop to taste them.

South across the bridge over the river Liamone

South across the bridge over the river Liamone

From here we descended on a minor road twisting and turning until sea level where we turned right and followed the coast road to Esigna, where we had lunch down on the beach, wriggling our bare toes in the warm sand. This was definitely not a typical CCC lunch stop. One of our number won’t forget it in a hurry. He stripped off to dive in the sea but was hauled out by a local worthy and told in no uncertain manner that this was not a nudist beach!

Lunch on the beach (photo Ph. Deeker)

Lunch on the beach (photo Ph. Deeker)

Just in case lunch on the beach had made us go soft (or that we start thinking this was a “holiday”), Phil imposed one of those little excursions he loves so much… a steep single-track road, the main point of which was to avoid 15km of main road. We came back to the main road unavoidably at Cargèse, and then followed the Tour de France Stage 3 route over the col de San Martino (433m) and on to Piana.

The less said about the long drag up the main road to Piana the better, but it was an essential transition before the second highlight of the day, the Calanche di Piana.

Calenche di Piana, an hour before sunset

Calenche di Piana, an hour before sunset

We became pure tourists goggling at the natural beauty, first on a scenic excursion towards the Capo Rosso to admire the Golfe de Porto, and then through the Calanche themselves. (The word in Corsican is already in the plural, so there is no “s” added). The Calanche are an extraordinary natural geological formation, mostly of pink granite. They are even more impressive when seen at sunset, but rather than attempt to describe them myself, I’m going to quote from Guy de Maupassant:

“I crossed the Calanche di Piana as night was falling. I stopped, astonished by these amazing rocks of pink granite, four hundred metres high, strange, tortured, bent, eaten away by time, bloody under the last fires of sunset and taking on all shapes like a fairy tale fantasy people, petrified by some supernatural power. I saw alternately two monks standing, of a gigantic size; a bishop seated, crook in hand, mitre on his head; prodigious figures, a lion crouching at the side of the road, a woman suckling her child and an immense, horned, grimacing devil’s head, no doubt guardian of this crowd imprisoned in stone.”

– Guy de Maupassant, Le monastère de Corbara (1880)

Translated by Marvin Faure

Calenche di Piana, an hour before sunset

Calenche di Piana, an hour before sunset

“It’s only weathered granite” remained the verdict of our geologist. Some are more romantic than others, I guess. Phil being one of these, he stayed out to catch the last, dying rays of the sun and came back with some stunning photographs. The rest of us were focused on more earthly matters.

Two stages left.

Stage 9 Porto to l’Ile-Rousse: 184km 2,595m

We started at first light with an initial climb out of the village, then a descent through the second part of the Calanche, sadly in poor light so the full beauty was not expressed. It was cool, not properly cold due to the proximity of the sea, but I was definitely glad to be wearing arm warmers and a thermal gilet.

Stage 9 profile

Stage 9 profile

For the first 50km we were back on the 2013 Tour de France route, including the col de Palmarella (408m). Not much chance of picking up the KOM then (not that I gave a moment’s thought to this at the time). My left Achilles tendon was worrying me. In spite of continuing with the Ibuprofen, it was really quite painful, no matter what I did. At the same time, riding at a very moderate endurance pace felt like a much higher effort than normal. Fatigue was catching up, and for the first time I began seriously to wonder if I would be able to finish.

The Golfe de Galéria

The Golfe de Galéria

An hour after leaving Porto the sun at last cleared the mountains and bathed us in a warm, orange glow, lifting my spirits. The Achilles didn’t seem to be getting any worse so until or unless it became unbearable I was going to carry on. We branched off the main road to Calvi, which went inland at this point, and continued on the coast road. It was a classic roller-coaster ride with lots of ups and downs. The ups were mostly in the sun and quite warm, the downs were mostly in the shade and quite cold.

La Baie de Nichiareto

La Baie de Nichiareto

We had the first feed station at a viewpoint on the coast, and then stopped for coffee at a café in Calvi. I took the opportunity for a chat with Phil who thought my Achilles tendon problem was most probably caused by increasing fatigue resulting in a degraded pedal stroke putting extra stress on the tendon. He might have been right because surprisingly it was least painful when I was climbing hard seated, and most painful when either standing or pedalling easily on the flat or on a descent, situations in which I was likely to flex my ankle the most.

Punta Rossa – the Red Point

Punta Rossa – the Red Point

The coffee was much needed because after our holiday ride along the coast we were now headed for the mountains. Ominously, Phil warned us that the major climb of the day was, in his view, the hardest of the week. When a man like Phil says something like this, you pay attention. A sense of foreboding came over me.

The climb to the col de Salvi (509m) served as a preliminary softening up. The road begins gently and then turns the screws as you approach Montemaggiore, where there are a series of steep switchbacks through the village itself. This isn’t the top though. It is barely half-way.

We enter the village of Montemaggiore

We enter the village of Montemaggiore

The climb got a little easier after the village, however, and once over the top there was a short descent followed by a rarity in Corsica, a long false-flat descent with a remarkably steady -0.2% gradient. We were heading east along the contours, so we benefited from a tailwind, accentuating the effects of the slope. Without making any real effort, I averaged 39km/h for 18km. By chance I was riding with our lady companion, and the time passed quickly as we chatted together, not forgetting to eat a honey waffle as we neared the climb.

The beginning of the climb we had been warned about was a rude awakening after the long high-speed stretch. There was a very sharp turn off the main road, the road doubling back and them immediately ramping up steeply. The Bocca di Battaglia (1,103m) was only the second climb we had seen in Corsica with kilometre markers for cyclists, and we stopped at the foot to examine the profile. This informed us we were facing 10.5km at 7.5% average. On the face of things this isn’t too hard, but as any cyclist knows an average gradient can hide a multitude of horrors and quite apart from the objective difficulty of a climb what makes it harder or easier is a combination of what has come before, the conditions on the day and how much you decide to push. When you are on the 8th stage of a Cent Cols Challenge, any climb becomes hard…

In this particular case, the climb is back-end loaded. The first half is relatively easy and the last half much harder: the gradient for the final 5km hovers around 10% and is irregular, often reaching 14% – 15% for short pitches. The weather was ideal, with the temperature around 14°C and a gentle side wind. The road was in a pretty horrible state in places. The workmen were on it, but inexplicably patching it by clumsily tipping concrete into the holes, leaving large lumps and making little effort to create a smooth surface. To me, this smelt strongly of a scam that no conscientious public works official could ever have approved. Not our concern however, and since there was no traffic we were able to avoid the wet concrete quite easily.

Forgetting (or ignoring) my early forebodings, I decided to make this climb a bit of a test. The reality was that my lowest gear (34-32) was such that trying to go up it in mid Zone 2 would have resulted in a very low cadence and correspondingly high force on the pedals and thus high stress on my Achilles tendon. Better to bite the bullet, and ride it quite a bit harder and thus at a more favourable cadence/torque combination. This seemed to work quite well as I managed to ride faster than many of the others, had little pain and even enjoyed the climb. YESSS!

Lunch on the Bocca di Battaglia (1,103m) – the hardest climb of the tour

Lunch on the Bocca di Battaglia (1,103m) – the hardest climb of the tour

Once again the beauty of the island was on full display. The views were truly stunning (I have now run out of superlatives). We had lunch on the col. It was not the most sheltered spot we could have found, but beat the hell out of any over-priced panoramic restaurant I could think of.

The “old man of the forest”

The “old man of the forest”

The descent on the other side was very long, much less steep and thankfully on a better road. I stopped for a selfie with the “old man of the forest”, and then found about half the group at a charming café a bit lower down in the centre of Belgodère, selling crêpes (pancakes) and home-made ice-cream and sorbets. There was an amusing moment when one of our group asked for a ham and cheese crêpe, only to receive a devastating put-down: Quoi? Je ne suis pas Bretonne, moi!” (What? I’m not from Brittany!) Luckily, I wasn’t interested in crêpes and enjoyed a delicious clementine sorbet.

Café stop in Belgodère

Café stop in Belgodère

After the stop I rode back to the hotel with three of the fast guys. I had to make an effort to stay with them on the flat, mostly with my right leg (Achilles playing up again), but then enjoyed a solid nine minute upper-tempo effort up the final climb with both legs. This was the biggest sustained effort I had put in since Stage 1, but I was past caring whether it was reckless or not. Apart from the wretched tendon, all felt good.

Our new hotel on the waterfront in L’Ile-Rousse was a real treat, the best of the trip! I could hardly believe it was the end of Stage 9: JUST ONE DAY LEFT!!!

Stage 10 l’Ile-Rousse to Bastia: 158 km 2,630m

The last day of this extraordinary adventure began in mixed fashion. My Achilles tendon felt tight and painful going up and down the stairs to breakfast, but breakfast was excellent with a good choice of everything I like. I loaded up on fruit, muesli, yoghurt, wholemeal bread, ham, cheese and excellent coffee, followed by a croissant with jam and a pain au raisin. After walking slowly back upstairs, feeling suitably replete, I gave the calf muscles a good stretch. The bike storage was a few hundred metres from the hotel so this gave an additional opportunity to gently stretch and warm up the tendon.

Stage 10 profile

Stage 10 profile

I don’t know if it was partly psychological or not, but such were the protests coming from my legs that going up the first couple of (very easy) hills felt like I was pedalling through an enormous vat of the jam I had enjoyed so much at breakfast. On the other hand, the pain in the tendon was manageable. We must be grateful for small mercies.

It was a much warmer day – for the first time in several days I was able to start without knee warmers, and didn’t need them throughout the day. We were headed up into the Cap Corse on a windless, sunny day and wouldn’t climb higher than 400m, so this was to be expected. On paper it looked like an easy day, at just 158km and 2,630m, at least compared to what had gone before, but nevertheless Phil hinted that one or two of the climbs might contain a few surprises…

The road from L’Ile-Rousse to St Florent

The road from L’Ile-Rousse to St Florent

We began by following a beautiful quiet road across to St Florent, with a nice easy 4% climb to the Bocca di Petraiolu (360m) and then spectacular views up the western coast of the Cap Corse. It was a lovely morning to be out cycling; no pressure, truly a moment to savour.

We stopped for our second breakfast in St Florent, much earlier than usual. For the first time I wasn’t hungry and ate very little, my hotel breakfast barely digested yet.

Coffee stop in St Florent

Coffee stop in St Florent

Leaving St Florent behind us, we passed through the vineyards at Patrimonio. The harvest was in and there was a strong smell of crushed grapes and the beginnings of the wine-making process. Patrimonio is probably the best known of the Corsican wines, and is reputed for its powerful, strongly flavoured red wines. Many years ago such wines were sometimes referred to pejoratively as “du gros qui tache” or even “pousse-au-crime” meaning the sort of strong red wine which stained your shirt or the tablecloth and could lead men to commit crimes, but those days are long gone and it’s now an excellent wine, as is the Muscat de Cap Corse, a sweet white wine served as an aperitif or with dessert.

After our loop through the vineyards the road headed north very close to the sea. There was almost no wind. The sea was very calm; flat but not quite glassy due to the remains of a swell. Towards the horizon, maybe 3 or 4 miles out to sea, the water was darker in colour so there might have been some stirrings of wind out there. A small boat made its way parallel to the coast, about a mile offshore: you could see its wake spreading out for as much as two miles behind it. I thought of my seafaring past and how much I used to enjoy pottering around in boats.

The Pointe de Negru, Cap Corse

The Pointe de Negru, Cap Corse

The road went up and down, in and out, following the coast. We were mostly 50m or so above the sea but sometimes dipped to sea level and sometimes climbed to 100m or so. We passed through the picturesque village of Nonza, high on a rocky promontory. There was an old tower built to keep watch over the seas to the west and an inviting café under the plane trees. I didn’t stop.

Nonza, Cap Corse

Nonza, Cap Corse

About 8km further on we left the coast road and started up a delightful little climb. The road was cut deeply into the side of the mountain, leaving the bedrock clearly exposed. Unlike the main part of the island, which is mostly granite, the rocks here in the Cap Corse are schist, laid down in the ocean many millions of years ago in multiple thin layers of sediment. The later movements of the tectonic plates heated, pushed and twisted the rock into the contorted shapes we can see today. I saw a fantastic variety of colours from white through all shades of grey and even green.

In places the softer rock has weathered away, leaving sharp and angular overhangs resembling slate. Just occasionally, smooth circular holes have appeared as if a giant ice-cream scoop has been used to hollow out the rock. Much of this is certainly natural weathering, but in places you can clearly see the neat semi-circular remnants of the boreholes the road engineers packed with dynamite in order to blast their way through the mountainside.

It was comfortably warm in the sun as I climbed steadily to the tiny village of Canari. I could well imagine the torrid heat one could experience here in mid-summer, followed by the delicious cool descent on the shady side.

My sensations are very variable, coming and going between pain and no pain, power and no power in the legs. Not much I could do about it except plug along, taking what came. My Achilles tendon obviously wasn’t getting any better, but neither did it seem to be getting significantly worse so I could but hope it would hold out.

Snake in the road! As thick as my finger, tapering to a bootlace at the tail, the snake lay there, unmoving, probably only just dead. It was bright green and black, about 60cm long, certainly a grass snake. There are no venomous snakes in Corsica.

The coast road on the Cap Corse

The coast road on the Cap Corse

We stopped for lunch on the col de Santa Lucia (381m). This is the crossing point between the western and eastern sides of the Cap Corse. It was a pleasant enough climb but rather an anti-climax after its much higher cousins that we had crossed earlier in the tour further down south. There was a sign to Seneca’s Tower, said to be the place where the Roman Stoic philosopher spent most of his time in exile in Corsica. If so, his Stoic beliefs must have stood him in good stead for the seven long years he was here: the contrast with the effervescence of Rome could hardly have been starker.

It was easy to miss the turn to the next col after about 4km of descent, so some did. It was a narrow road up through a forest which then opened out with uninterrupted views across the sea to the east, and our first sight of the Italian island of Capraia. Down we went all the way to sea level, and then headed back south along the eastern coast of the Cap Corse.

One couldn’t help noticing that the houses here are built very differently to the main part of the island. Instead of large blocks of dressed, square-cut granite, they are built of schist. Since this splits easily and is almost impossible to cut cleanly, the rough-finished stone walls are then filled and plastered over smoothly with stucco and painted, mostly in pastel colours of cream, yellow or pink. The paint then fades and flakes over time to give a timeless and charming sun-baked Mediterranean feel to the houses.

Tour de Losso, on the eastern side of the Cap Corse

Tour de Losso, on the eastern side of the Cap Corse

During the 15km we rode along the coast I had the two Italian islands of Capraia and Elba constantly in view on my left. Elba is the larger and higher of the two and was sporting a topping of white clouds. If the name is familiar to you it’s most probably from history: Elba was the site of the first of Napoleon’s two island exiles. He stayed here only 10 months before escaping in February 1815 and briefly taking back control of France. The battle of Waterloo put paid to that 4 months later and this time he was put away for good, on the island of Saint Helena thousands of miles away in the south Atlantic.

I was nearly there but there were still two more climbs to get over. The first was unexpectedly hard, with a kilometre or so at 12-13% before topping out at 280m and precipitating us back down to sea level again. The second and Yes! the final climb brought us to an impressive view-point at San Martino, high above the port city of Bastia where our adventure had started and was now to end.

The port of Bastia, from our final climb

The port of Bastia, from our final climb

There was a lovely surprise at the view-point: Mateusz was waiting there for us, with ice-cream!

Ice cream eaten, photos taken, congratulations given, there was nothing left but a vertiginous descent to Bastia and the hotel, followed by a slow return to reality.

Epilogue

I am very proud and happy to have completed a Cent Cols Challenge. It was a great group to cycle with, quite closely matched in cycling ability and excellent company. If I have written little about the individuals concerned and haven’t mentioned any names, it is to protect their privacy. I made many new friends and I’m sure our paths will cross again.

Of the 13 riders who started, we were 10 to finish and be added to the CCC “Wall of Fame”. This is a higher proportion than normal, perhaps due to the excellent weather and a route acknowledged to be less challenging than some of the others. (Yes, indeed: the mind boggles). If you have read this far you will know these are seriously tough events that demand serious preparation. Sometimes a cliché says it best: fail to prepare = prepare to fail.

Phil Deeker organised the whole event in a highly professional manner, achieving what was for me the perfect balance between the challenge laid down and the support provided. The choice of routes was outstanding, the hotels were fine and the occasionally average quality of the meals more than made up for by the exceptional quality of the two daily feed stations.

At the time of writing twelve days have passed since I last swung my leg over a saddle. I certainly haven’t been inactive and have been swimming several times as well as restarting my programme of strength & conditioning and Yoga. I can feel that my Achilles tendon is still not quite right so I’m in no hurry to get back on the bike. I would have taken a 2-3 week break in November anyway, so I have just slightly brought this forward.

This was, by a considerable margin, the most cycling I have ever done in a 10-day period. I have analysed the ride from a coach’s point of view and formulated a set of recommendations for anyone tempted to ride their own Cent Cols Challenge.

About the Cent Cols Challenge

Cent Cols Challenge events are designed and managed by Phil Deeker. There are as many as ten events per year, in regions ranging from the Pyrenees to the Ardennes, from Corsica to the Alps and from the Apennines to the Dolomites. While they vary in difficulty, all are designed to include at least a hundred cols. The difference comes down to the terrain, the quality of the roads and how steep the climbs are, with the weather an ever-present imponderable.

Speechless. It makes my Haute Route (7) day event look like an afternoon ride. Beyond anything I would even consider. Take care

Fantastic read Marvin, you are obviously a good writer as well as a (more than) good rider!

Thank you Michael for the kind words! Much appreciated.