I have written this article to illustrate the rapid detraining that takes place when you are forced to stop training for a lengthy period, and the long road back.

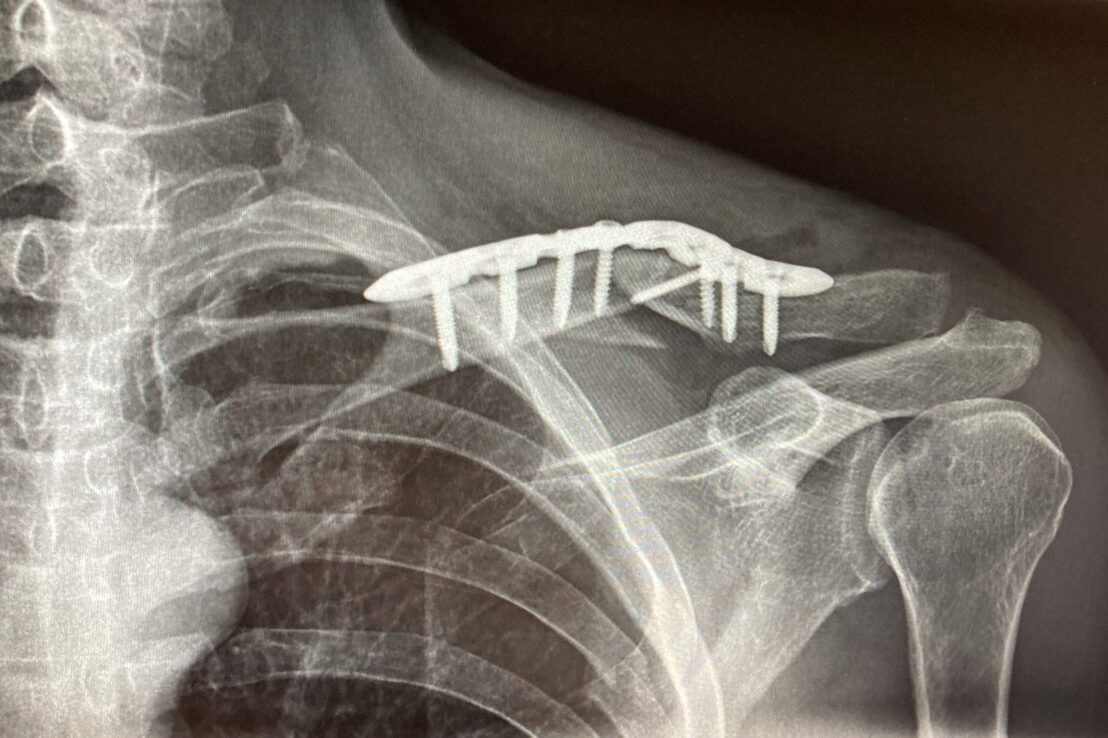

My accident took place on July 2nd 2022. I broke my collarbone (in three pieces) and badly broke four ribs as well, with numerous cuts and contusions. My helmet was broken but saved me from a head injury or concussion.

The first 21 days

The first reaction to a broken collarbone is to do nothing and hope it mends itself. Similarly, there’s nothing one can do about broken ribs except grin and bear it. I took a heavy course of pain killers and moved as little as possible throughout this initial period.

I had an X-Ray to monitor progress on day 8. Unfortunately, this showed I needed an operation, which took place on Day 12.

My first physiotherapy session was on Day 16. These have been absolutely crucial to my recovery. In this first one the focus was on releasing tight muscles in my back, shoulder and neck that were hampering movement and causing pain, while learning some very minimal movements with the arm to start the re-education process.

Throughout this three week period I was constrained to move as little as possible, and was of course unable to do anything resembling exercise. I was therefore rapidly detraining. Research has shown significant changes after 21 days of detraining, including a rapid reduction in plasma volume which leads to a decrease in the heart muscle, reduced stroke volume and thus reduced transport of blood around the body. In addition, changes in mitochondria function begin to affect muscle endurance.

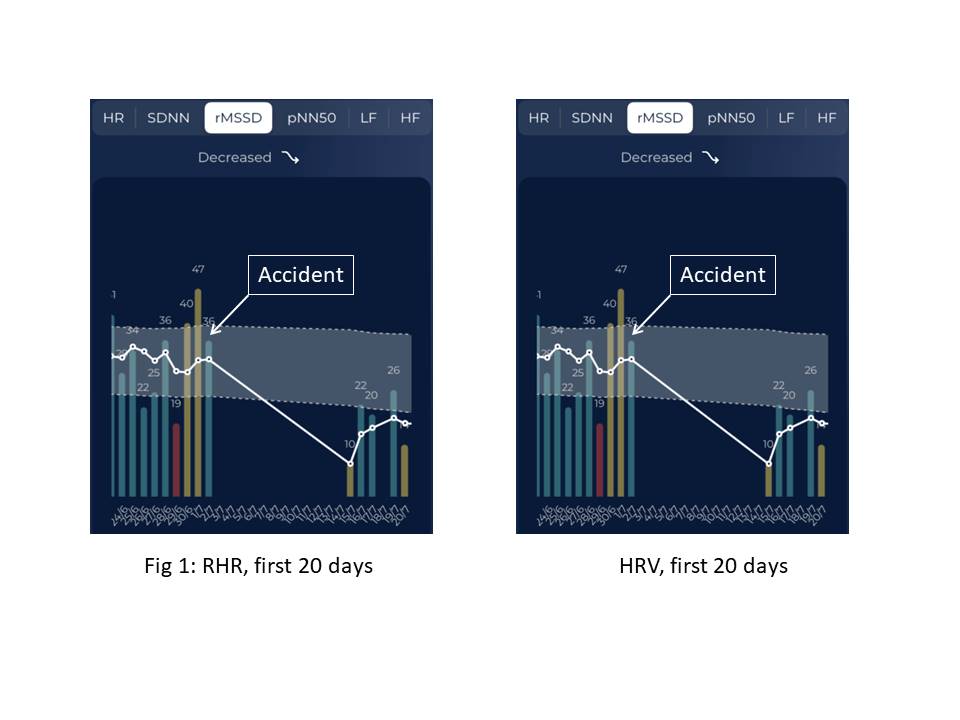

The only measures I was able to take myself were a few RHR and HRV readings (Resting Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability), taken on days 13-18. These showed a sharp increase in RHR and a sharp decrease in HRV from my normal range pre-accident, confirming that my body was working hard to repair the damage.

Day 22 to Day 60

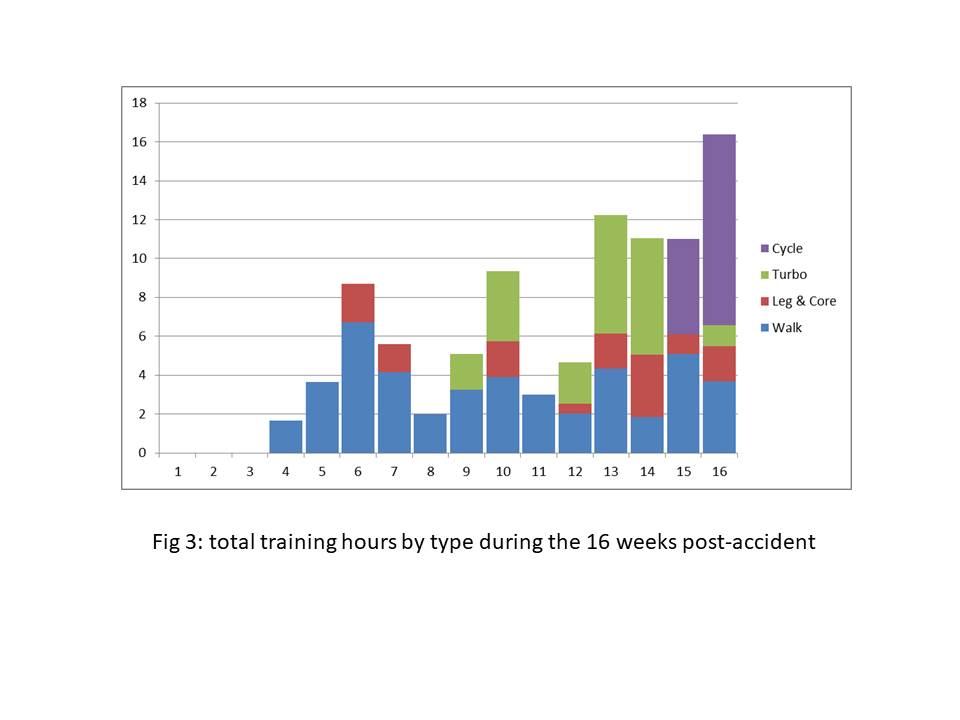

After more than 3 weeks of complete detraining Day 26 was the first day I felt ready to begin some limited but regular exercise again. I started by walking barely a kilometre in just 20 minutes, and then progressively extended this to 2km, then 3km, then almost 4km in 50 minutes. It wasn’t the legs that were holding me back of course, but both general fatigue and residual pain in the shoulder and ribs.

Weekly physiotherapy sessions were important to continue releasing the many different muscles and fascia which play a role in moving the arm and shoulder. Most of these were still very tight, in a normal defensive reaction to the injury.

Every 2 or 3 days I did a series of leg strength exercises, increasing the number of repetitions and sets very progressively. By day 50 I was up to a one-hour walk every day and a short (30 min or less) leg & core strength workout every 3 days.

Day 61 to Day 99

The big step forward on Day 61 was to sit on a bike and turn the pedals again for the first time since the accident. The main concern was my ability to take weight on my shoulders. I therefore kept the first turbo session to just 35 minutes, all in Z1 (below 65% HRmax), sitting up every few minutes to take the pressure off my shoulders.

I did a total of 8 sessions in the next 10 days, with the longest being 48 minutes.

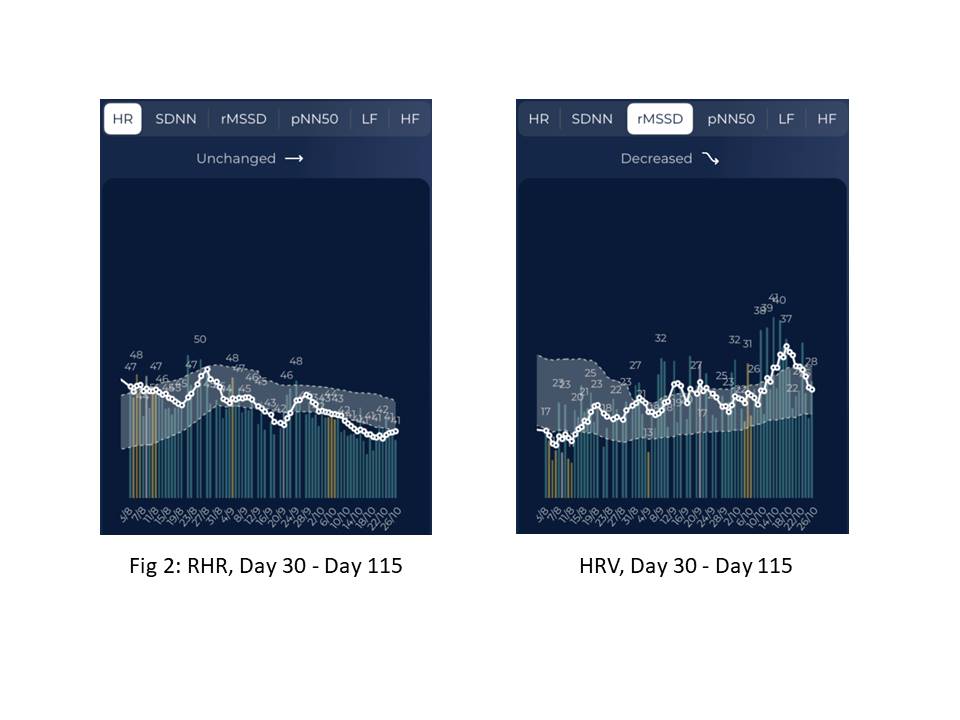

The effects of two months of detraining were clearly visible in my HR vs. power data. Whereas before the accident I would do a 1h recovery session at around 140W and 90-100bpm, I was now finding my HR to be 15bpm higher for a power output which was lower by 15-20W. At equivalent power, my HR was 20bpm higher.

At the same time my cardiac drift (or aerobic decoupling) was in the range 5-8%, again much higher than what it was pre-accident, when I was able to ride for more than two hours at 160-180W with essentially zero drift.

For the next month I progressively increased time (but not intensity) on the turbo, time spent walking and time spent doing leg and core strength exercises. On the turbo I went first to one hour, then 1h20 and even 1h45 on Day 94. On Day 98 I tried some intensity for the first time, with 7’30” in Zone 4, which took me to 90% of HRmax.

My total training in the last two weeks leading up to 99 days post-accident was 11h per week, including roughly 6h on the turbo, 4h walking and 2h of leg and core strength workouts. My HR response was improving, but was still 15bpm above where it used to be at recovery pace. My RHR, on the other hand, had now dropped to only 2-3bpm above the normal range pre-accident, and there was a corresponding improvement in HRV.

I continued with regular physio sessions, now mostly focused on mobilising and strengthening the shoulder.

Day 100 to Day 115

Day 100 to Day 115

Oh happy day! Day 100 was coincidentally the day of my first proper ride since the accident. It was a lovely day and I was able to enjoy a 2h30 ride outside. This was half an hour longer than intended and was quite enough: I was feeling tired in the arms and shoulders by the end.

I did two more short rides out that week, as well as 5h of walking and 1h of leg and core strength work, for a total training time of 11h.

In week 16 my total training time reached 16 hours, made up of a bit less than 10h cycling outside, 1h on the turbo, 2h of leg and core strength workouts and 3h30 walking. My RHR and HRV continued their improvement and are now close to my pre-accident normal levels. Importantly, my HR response to a 1h steady ride on the turbo also improved, as I managed 129W at 101bpm and a cardiac drift of only 0.6%.

For context, in the three months prior to the accident (with the exception of a 2-week taper) I was training for an average of 17h per week, nearly all on the bike, with a 30-45 min leg and core strength workout and an occasional 30 min swim. At the time I didn’t record my walks, but they were at most 2h per week..

At the end of this period I felt ready to tackle a 3h ride, which I did on Day 118.

Next steps

During the next three months I intend to stabilise my average training load at around 15-16 hours per week (including cycling, swimming, walking and strength workouts). I will be continuing to monitor my readiness to train using HRV, perceived fatigue and the SFT test (read here for more on this), and will adjust my training plan based on my body’s readiness to benefit from the load.

My goal is to recover and even improve my pre-accident aerobic condition. This will mean a high volume of low-intensity work combined with a small amount of high-intensity to recover some anaerobic fitness through the winter period, and then adding more event-specific sweet-spot and high-intensity work in the spring and early summer.

If all goes well, by late spring of 2023 I should be back to normal!

For more on detraining, read here: How much fitness do you lose when you stop training?

Very helpful summary of your journey Marvin. it helps me as I recover from my own, thankfully less serious, accident. Thanks

Thanks Michael, good to hear it was useful!

Thanks for sharing. Great determination.! Best wishes for getting back!

Thank you Jürgen!